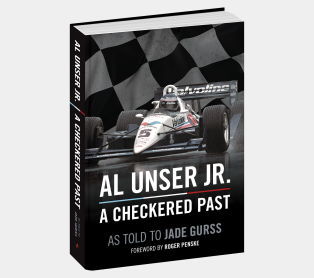

A Checkered Past: Reaching for Speed

Winning came naturally for Al Unser, Jr. He had a gift for finding the fast line on the track and he possessed a boisterous and lovable personality. Fans and the press adored him, but behind this affable persona, his appetite for drugs and alcohol was destroying his private life. Unser's battle to climb out of that cave is one of the great stories in motorsports. A Checkered Past is an unblinking story of triumph, tragedy, and the road to recovery. In this excerpt from the book, catch a glimpse of the struggles to gain speed.

What would you do if your ultimate fear—your worst nightmare—was in front of you? How would you face it?

From the opening day of practice at Indianapolis in 1995, the sledge-hammer was back. All of the issues from testing had returned. We were slow. The cars didn’t handle in the corners, and, even worse for a driver’s confidence, were unpredictable.

The Penske crew chiefs and engineers had breakfast before the third day of practice, and several of them got into an argument and one threw coffee on the other. The tension was unbelievable. At the daily meeting that morning in the Penske garage area of Gasoline Alley, there was such an atmosphere—the mood was so dark it was almost unbearable. It blew everybody up. No one could think clearly. Tension was in every crevice, in every corner, in every inch of that garage. It usually seemed big and roomy, but the walls felt as if they were creeping in. We were panic-stricken.

Part of what makes the Indianapolis 500 so great is the fastest thirty-three cars in qualifying start the race. If you are thirty-fourth fastest, you go home and come back next year. You have to perform. The rules don’t care Roger Penske’s team had already won the race ten times or that Roger had at least one car on the front row in twenty of the twenty-seven years the team had entered. Emerson and I had won the last three Indy 500s, four overall. In the long history of the race since 1911, a few team owners had spent their way in by buying a team or a car that had already qualified, but you only got a starting spot on merit. Speed is what matters.

We had no speed. It was so beyond all of our imaginations; it had never been spoken of. No one could get the thought out of their head that we might miss the show.

It wasn’t just one Penske car, it was all of them. Emerson and I both had a primary car and a backup car. (At Penske, the cars were close to identical, so “backup car” was a term that didn’t reflect if it was better or worse.) They all had the same problem: the car would turn into the corners too quickly, but then the front tires would give up and the car pushed from the middle to the exit of each turn. We worked on solving the push, but then it turned in too quickly. When we tried to address the turn in by settling down the rear end, the front end handled so bad it was dangerous. Suddenly, you were out of the groove and into the gray. You did all you could to keep it out of the wall at 220 miles per hour.

Inside the car, the driver could make several adjustments, but no matter how much we moved the settings, it seemed to make no differ- ence. The cornering issues killed the tires. It was diabolical and scared Emerson and me. We were fucked.