"Land Speed Record For Women Broken"

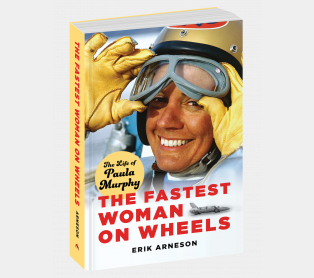

The following is an excerpt from The Fastest Woman on Wheels: The Life of Paula Murphy by Erik Arneson. A fearless pioneer and a versatile and gifted driver, Paula Murphy was the first woman to pilot a jet car to a Bonneville Salt Flats speed record, the first woman to make laps at famed Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and the first woman to secure an NHRA Funny Car license. In this excerpt, read about how Paula Murphy made history during her land speed record run at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Lyndon Johnson was president. Bonanza was the number one show on television, and the Beatles had just wrapped up their first US tour after famously appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show earlier in the year.

As an eventful 1964 neared its close, a little more than an hour from the Nevada-Utah border-straddling town of Wendover, a thirty-six-year-old single mother of one, who grew up modestly in Cleveland, found herself unassumingly on the brink of history as she stared alternately at the vastness of the famed Bonneville Salt Flats and back again at a homemade, jet-powered hot rod she had never laid eyes on before that moment.

“When I got [to Bonneville] and saw the car for the first time, I said to myself, ‘Hmmm, do I really want to drive this thing?’” recalled Paula Murphy, now ninety-five and living in California.

Her job appeared simple enough—point it straight and go fast. After all, there was nothing around for miles but salt. However, there were more than a few impediments to completing the high-speed task. The first and most obvious—she didn’t fit in the car. The cockpit had been designed and built for a man with larger proportions. But with the aid of a strategically placed pillow or two, Murphy, who had been making her name on the California sports car racing circuit for several years, piloted speed pioneer Walt Arfons’s open-cockpit, jet-powered Avenger across the Bonneville Salt Flats for a two-way average speed of 226.37 miles per hour.

Looking to take advantage of growing national interest in the ongoing automotive speed wars on the salt—and all of the activity in the advertising arena that surrounded it—motorsports moverand- shaker Andy Granatelli brokered a deal with Arfons via an STP sponsorship. Granatelli enlisted Murphy. Her pay for the effort: ten dollars for every mile per hour, plus expenses. A day later, and more than 2,000 miles away, the New York Times ran an easy-to-miss, five-paragraph story in the middle of page forty-two with the two-deck headline:

Land Speed Record

For Women Broken

There were plenty of reasons along the way to back out or say “no, thanks,” but Murphy fulfilled her commitment, never outwardly flinching throughout the hastily-thrown-together effort. Fortified by a Midwestern work ethic instilled by her father, Murphy stayed on task.

“That’s the only way,” Murphy reflected the following year for Modern Rod magazine. “If I had time to sit around and think about it, I might have chickened out. Of course, I was scared.” With pre-run instructions that Murphy recalled included little more than, “on the right is the accelerator and on the left is the brake,” she climbed in.

Additional explanation, however brief, was given, and simple controls included a brake pedal on the floor and three levers on the left side of the cockpit—the throttle, the afterburner, and the parachute brake. Due at least in part to Murphy’s inexperience, the deteriorating Bonneville surface conditions, and, in all honesty, to keep her away from any of the men’s speed records, Murphy was instructed not to use the afterburner.

“In order for me to reach the brake pedal, they had to stuff a big pillow behind my back, which raised me up in the seat [and above the small visor], and I got the full blast of the wind when I was making the run,” Murphy said. “The strain on my neck and the force of the wind was quite a distraction.”

According to an April 1965 article in Floyd Clymer’s Auto Topics magazine, Arfons was confident Avenger was a safe ride for Murphy, who would be piloting a jet-powered car for the first time. Powered by a 2,000-plus-pound Westinghouse J46 jet engine designed for navy airplanes, the hot rod, which looked like little more than a chair in front of a horizontal stack of beer kegs, had made nearly a hundred dragstrip runs over the quarter mile, hitting 200 mph or better on every run—without incident.

Avenger was designed and constructed in Arfons’s Akron, Ohio, shop on Pickle Road, in a space he shared with his halfbrother and fellow speed chaser, Arthur. Described by Sports Illustrated writer Jack Olsen, Arfons’s workspace was a “dark place with grimy windows looking into a clutter of jet engines, shelves lined with aircraft instruments and cannibalized parts of old automobiles, airplanes and trucks.”

The hot rod on the salt that day was born much like Frankenstein’s monster in a garage not unlike many others scattering the American landscape, albeit with the uniqueness of a few jet engines. The other distraction for Murphy—a soaking wet course and continuing precipitation at Bonneville. With a mixture of rain, snow, and hail falling on the course the night before, there was some doubt if the Arfons group would get a chance to make any passes at all.

“The [Avenger] had never been run more than a quarter of a mile. I only had about three miles of usable salt,” Murphy said in a July 1970 article in Hot Rod magazine.

Distractions and safety concerns aside, and with Granatelli’s giant STP stickers slapped to any available space on the car, it was time to get things started. Driver Bobby Tatroe, on-site to both pilot Arfons’s Wingfoot Express and act as drag strip pilot for Avenger, gave the hot rod a test run, clearing the way for Murphy’s attempt. Murphy continued her preparation, putting her trust in the team, while noting that without jet car experience, it was mostly, “monkey see, monkey do.”

“Bobby Tatroe showed me all the things to do, and he set the throttle,” Murphy said in Hot Rod magazine. “It had a hand throttle and he must have set it at about 80%. You sit there with your foot on the brake while the power builds up, and when a little red light comes on, you’re supposed to go. So, when the light came on, off I went. I figured I could just sit inside and go along for the ride. Well, that car was all over the course. Scared me to death.”

Murphy’s historic effort was recorded in detail in an unattributed feature, most likely with contributions from STP PR, that ran word-for-word in multiple publications, including the February 1965 edition of Modern Rod and as an April cover story for Floyd Clymer’s Auto Topics magazine: “After five minutes of final instructions, Paula took a deep breath and told the USAC man with the walkie-talkie that she wanted to run through the course to the other end. She asked to be timed, but warned it would not be a fast run, ‘only practice.’”

The whine of Avenger’s jet engine was not unfamiliar to Murphy, having seen similar jet cars run at local drag strips. Being strapped inside one, however, was a little different. After belching out a ten-foot flame, the power in the screaming engine began to build, and according to the article, Murphy released the brake and “disappeared into a haze of salt, dust and spray.”

The wet salt struggled to hold the hot rod, with Murphy going into a two-city-block-long fishtail before using the parachutes in an attempt to correct the trajectory. When she finally came to a stop, Avenger was parked in four inches of water and the chutes were soaking wet.

Her proud response, once USAC officials, her crew, and media reached the car: “How’d you like them apples?”

The call from USAC came across the walkie-talkie. Murphy’s first-pass speed was 236.00 mph. But to set the record, she’d have to pack up the wet parachute and make the required return pass. Her confidence shaken, but still intact, Murphy replied, “Let’s get going back the other way.”

Within minutes, the car was checked out and ready to run in the opposite direction across the weather-soaked surface. Running a little less throttle on the return run, Murphy clocked in at 217.50 mph for the second flying mile, giving her a two-way average speed of 226.37 mph.

“I didn’t scare myself quite so much that time, but it’s still a mighty quick trip,” Murphy said in the article. Joe Petrali, chief steward for USAC and FIA, ran up with her averages and asked if she wanted to try another run back to tie up the slow one and thus get a faster two-way average.

“I think that’s enough for one day . . . I’m satisfied . . . I know I can do it . . . and we do have a new record.”

“That’s a smart decision,” Petrali answered.

Murphy had her record. Granatelli had his publicity.