Trouble at Riverside International Raceway

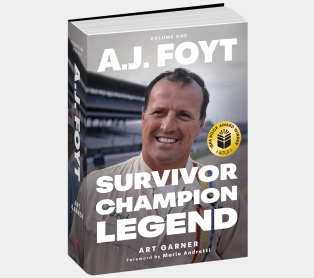

The following is an excerpt from A.J. Foyt: Volume 1 by Art Garner. Anthony Joseph “A.J.” Foyt Jr. is one of the greatest race car drivers in history—some would argue the best—and he has the statistics to back it up. Numbers alone can’t begin to tell Foyt’s story. Through tireless research and extensive interviews with the biggest names in motorsports, author Art Garner has compiled an unprecedented look at the life and career of one of America’s most popular sports heroes. In this excerpt read about Foyt's crash at Riverside International Raceway in 1965 and his subsequent recovery.

While a road course, the most dramatic feature of Riverside International Raceway was the 1.1-mile back straightaway that doubled as a drag strip, the first half of which was downhill. Stock cars topped 150 mph before braking hard for Turn Nine, a nearly flat 180-degree right-hander, bringing the course back to the pit straight and the start/finish line. The outside of the turn was guarded by boilerplate steel guardrails backed by sunken telephone poles. Nine drivers had been killed at the track since it opened in 1957, four of them in Turn Nine.

Foyt’s ride was a new Ford Galaxie, built and entered by Holman-Moody, “one of the most powerful forces in racing in the 1960s.” In addition to building most of Ford’s stock cars for other teams, it ran its own two-car operation and was getting involved with Ford’s sports car program. It was both the front and back door to Ford’s stock car racing operations with Ralph Moody, a former NASCAR driver, running things at the track and John Holman overseeing the business operations.

For Riverside, Foyt was paired with team leader Fred Lorenzen and newcomer Dick Hutcherson, a rookie making the jump from IMCA and ARCA. Lorenzen was one of NASCAR’s elites and a bit standoffish, but A.J. immediately bonded with Hutcherson. It was the first step in a relationship that would grow and prosper in the years ahead.

Foyt’s car was No. 00, which raised eyebrows as it looked the same upside down as it did right side up, considered unlucky by some. Foyt wasn’t concerned, asking only that a submarine belt be added to the safety harness, a request Moody, who’d pushed NASCAR to adopt the feature, was only too willing to meet.

Dan Gurney and Foyt turned in the two fastest times during practice, both breaking the track record, but they were relegated to starting eleventh and twelfth as the speeds came a day too late for the pole. After celebrating his thirtieth birthday the night before the race, Foyt chased Gurney from the start. The pair worked their way through the field and into the top spots when Parnelli Jones, who’d led early, dropped out. From there Gurney and Foyt battled nose to tail, Foyt pulling alongside at times, but never able to complete a pass, eventually spinning and falling behind the leader.

Gurney pulled away to a fifty-second lead with only twenty laps remaining when a caution flag bunched the field as allowed under NASCAR’s rules. Gurney’s teammate Marvin Panch was second, followed by Junior Johnson and Foyt. There was time for one more run at the leader.

Pulling to the inside of Johnson at the end of the backstraight on lap 169 of the 185-lap race, Foyt waited until the last moment to brake for Turn Nine. He’d struggled with the new self-adjusting brakes throughout the race and this time “the pedal went clear to the floor.” He tried pumping the brakes to build pressure without success and then considered trying to make the turn but, he said, “I knew I’d take Johnson and Panch with me if I did.”

“I wondered what happened,” Johnson said. “[Foyt] came shootin’ by me forty miles an hour faster than I was going.”

Foyt veered to the inside of the course, where the ground dropped thirty-five feet away from the track surface so quickly and steeply it was known as the “Turn Nine Canyon.” The car left the track at an estimated 100 mph and flew about forty feet in the air before disappearing into the canyon. The first impact popped the windshield out of the car and kicked up a huge dirt cloud, the car emerging in a series of rapid end-over-end flips. The Galaxie stopped just short of the track, pointing at the middle of Turn Nine, having carried so much speed it nearly hit the cars Foyt was trying to avoid. Panch would say he felt the impact of the car’s final flip.

“The only thing I could hear was a strange wheezing, then I realized it was my gasping for air. That’s all I remember.”

—A.J. Foyt

“I was watching from the pits and I could see right away what he was trying to do,” said Leonard Wood of the Wood Brothers team and co-owner of the cars driven by Gurney and Panch. “His car just started cartwheeling. It was a terrible accident. He went so far he nearly came back up on the track and hit Panch.”

The first to arrive at the car found Foyt unconscious, covered in dirt, and hanging limp but secure in his seat. Someone supposedly told others not to rush, the driver was dead. The wreck quickly attracted a crowd and another person noticed movement in the cockpit. A Holman-Moody crewman arrived on the run and climbed into the car, asking Foyt if he was okay. He nodded, dazed and unable to talk, but very much alive.

One of the myths surrounding Foyt—and Jones—is that Parnelli was the first to spot movement, climbed in the car, and cleared dirt from Foyt’s mouth so he could breathe. Extensive media reports of the day mentioned only the Holman- Moody crew member and early biographies of Jones make no mention of the incident. With good reason. Jones says it never happened.

After dropping out of the race, Parnelli was watching from the entrance of Pit Road, near the exit of Turn Nine. Like others, “he ran to see what he could do, which amounted to watching the rescue crew extricate Foyt and load him in an ambulance.” No one knows how or why the story of his expanded role in the rescue started.

Foyt says he’d obviously heard and repeated the Jones story, but was in and out of consciousness and has no actual recall of the accident’s immediate aftermath. “The only thing I could hear was a strange wheezing, then I realized it was my gasping for air,” Foyt said. “That’s all I remember.” He did recall the moments before the crash in various accounts over the years.

“You don’t exactly reason it out,” he said soon after the crash. “Hell almighty, there’s no time for debate. If you’ve been doin’ this thing for a while, you get the picture right away and you react, almost by instinct.

“Maybe I could have missed Johnson, but not Panch. If I’d of hit him from behind, I’d have rode him up into the wall. I might’ve gotten away with it, but I don’t think he could’ve. I didn’t think I could cut underneath them and stay on the track, but that’s what I figured I had to do, so wham, away I went. I hit a bump though and got airborne. That’s about all I remember.”

Taken to Riverside Community Hospital, initial reports that evening downplayed Foyt’s condition, saying he’d suffered a “foot injury, cut hand” and had some chest pain. Those coming to check on him discovered otherwise. Richard Petty was one of the first to arrive at the hospital. He’d been unable to drive in the race because of the Chrysler boycott, driving the pace car instead.

“It was a bad wreck,” said Petty, who was on his way to the Los Angeles airport. “Before we flew out, me and Dale [Inman, Petty’s cousin and crew chief] went by to see him at the hospital and he was pretty beat up. It looked bad. But he’s a hard head.”

“He is a horrible patient. Horrible. It was like, God, I’d almost rather do this myself. I’m a lot better patient than him. He’s no fun when he’s sick."

—Lucy Foyt

Jones and Agajanian also visited the hospital. The heavily sedated Foyt remembered little of those first hours, only that he was desperate to reach his mother, who’d recently suffered a heart attack. He wanted to assure her that he was okay.

“I remember coming to in the hospital, not really coming to, but off and on. I kept saying I need to talk to my momma. They finally got her on the phone and she said, ‘Ah honey, are you real bad off?’ And I said, ‘Momma, I’m fine. I’m bruised up pretty good, but I just wanted you to hear my voice. I’m fine. Now I’m tired and I’m sleepy and I’ll talk to you later,’ and I went back out.”

It wasn’t until later in the week that the extent of Foyt’s injuries was known. Lucy arrived from Houston to find the left side of his face and chin scraped and cut where his helmet twisted during the crash. He had two black eyes. He complained about pain in his lower extremities and she gasped when she lifted the sheet. He was black and purple from the waist down. The submarine belt had worked, but had left its mark.

Another round of X-rays discovered that he’d cracked his ninth vertebra in addition to the compound heel fracture. The broken back had been hidden in earlier X-rays by swelling and was the cause of the pain. He was also diagnosed with a bruised aorta. He’d been lucky, doctors said—an inch or two either way and he’d have been paralyzed, or worse. They said the upcoming races at Daytona were out, and Phoenix and Trenton were doubtful. Even Indianapolis was questionable.

It took ten days for Foyt to convince the Riverside doctors he could travel. Ford sent one of its company planes to move him to Houston, where he entered Memorial Hospital. It was another ten days before doctors there let him go home.

It was Foyt’s first extended “sheet time,” as he called hospital stays. Once at home, Lucy discovered what doctors and nurses already knew.

“He is a horrible patient,” she said. “Horrible. It was like, God, I’d almost rather do this myself. I’m a lot better patient than him. He’s no fun when he’s sick. If I could send him off, that’s what I would have liked to do. But he always got home as soon as he could.”