Weathering Storms

This article was originally published as a feature in the Ageless Iron section of Successful Farming magazine, where Lee Klancher is a regular contributor.

Landing in the Quad Cities in January was a shock. I exchanged Austin’s seventy degrees of sunshine for sub-zero air choked with a haze of snow and freezing rain. In fact, our plane sat on the runway for thirty minutes waiting for a crew to de-ice our gate.

I was in the Quad Cities starting work on a new book project. While I was there, I planned to speak at an American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) meeting held at St. Ambrose University. As I stood at baggage claim, my phone rang. It was David Smith from ASABE, calling to say that the university had closed due to inclement weather, and the meeting was cancelled.

That night, nearly ten inches of snow fell, and the next morning I walk out to the hotel parking lot to discover my rental car buried in snow. After clearing the windows, I discovered the car was stuck. I began the time-honored practice of patiently rocking the two-wheel-drive sedan back and forth, and a tall young man in military camouflage knocked on my window.

“I’ll push you out if you loan me your ice scraper,” he said. Done deal.

As I slithered my rental car along River Drive in Moline, it occurred to me that perhaps the world was trying to send me a message about the wisdom of taking this trip and, more ominously, putting together the book that inspired it.

Such doubts are part of the process when you start to transition from a concept to gathering the research, images, and stories that will form a book. Each new find is a piece of the puzzle. Until you have a good body of puzzle pieces, understanding how the work will flow together is challenging. That morning in Moline, my puzzle of a book was a few disparate pieces scattered haplessly on a large table. My cold-numbed brain was struggling with where the rest of the pieces would come from and how they would fit.

The sheer beauty of steam coming off the bits of open Mississippi took my mind away from the puzzle and led me to wonder how many agricultural innovators had driven this same road on their way to engineering facilities and test sites. That in turn led me to marvel at the incredible amount of agricultural history housed within this cluster of four cities situated on the Iowa and Illinois border.

The story I know best from this area—and the topic of my cancelled talk–is the evolution of the rotary combine. The technology took a century to become workable, and its creation is a study in adversity.

The idea of the rotary separation of grain germinated in the 1800s, and one of the early innovators was Anson Rowe of Atalissa, Iowa—a small town only thirty-seven miles west of the Quad Cities. Rowe patented a rotary grain separator in 1862. It was never produced.

Many inventors would struggle to make this technology work. The brilliant and famously independent inventor Curtis Baldwin tried, with a patent in 1936. He and his six other ventures would all fail to produce. His company, Gleaner, was sold to Allis-Chalmers and some of Baldwin’s patent rights were sold to Massey-Harris. Both brands are of course now owned by AGCO. Baldwin died in 1960 in California, never having seen his rotary dreams bear fruit.

One of the most tragic and interesting stories in early combine history is that of Curtis Baldwin, who developed a series of innovative machines and tried to market them with a series of ultimately doomed companies. Baldwin’s designs were sold to Massey-Harris shortly before he died. Today, fewer than a half-dozen Curtis harvesters are in private collectors’ hands. This patent is for one of his early combines that used rotary separation. Photo courtesy of US Patent Office

More independent companies—notably Harvestaire—would try unsuccessfully to build a rotary grain separating combine. In the early 1950s, Elof Karlsson and Mel Van Buskirk, two International Harvester engineers began experimenting with rotary separation technology.

The men came to IH and ended up working together on the advanced engineering team, a group that had the creative freedom both men treasured. Van Buskirk recalled on his first day he was told to “find something to do.” What he found was Karlsson, who was a prolific, independent, and famously outspoken engineer.

In 1955, the two led the engineering team that built several experimental combines using rotary separators. In 1958, Stuart Pool came in to lead the advanced engineering group. He nixed the rotary program due to dishearteningly poor performance.

In the early 1960s, the IH team’s development of rotary separation for corn and grain began in earnest. Inside a garage with blacked-out windows, thousands of hours of development time were logged. In the hundreds of pages of notes and reports to management, engineers repeatedly stated they thought the technology would be ready to introduce in a few months or years.

At one point, the engineering teams ran more than six hundred tests over an eight-month period and noted no improvement at all in how the grain was flowing through the separator. They did, however, optimistically state that they had learned quite a lot.

The project that began in the mid-1950s would not see production until 1976. The amount of patience and dedication required by these engineers is awe inspiring.

The No. 10 was the second experimental rotary combine. Harvester tested this machine from 1955 to 1958. The threshing cylinder was conventional, but the separator was a rotary, three-cylinder design created by Mel Van Buskirk. The rotors were arranged crosswise in the machine. The project was killed in 1958 when Stuart Pool took over Advanced Engineering and decided rotary separation technology wasn’t worth the investment. Photo courtesy of Dave Gustafson/Case IH

Back in Moline, I was grinding away on my project when my phone rang. It was David Smith from ASABE calling to say he had been able to reschedule the meeting for the next night and I would be able to give my talk. My spirits lifted, as I had been looking forward to the time with agricultural engineers.

That evening, the small room was full of engineers, some of them the very men who had struggled and prevailed to create the original Axial Flow combine. As always with such events, I learned a few more things and added a piece or two to the puzzle.

One of the closing stories I told that evening was that in the aftermath of the IH introduction of the Axial-Flow combine, John Deere put together a program to evaluate what it would take for them to develop a competitive technology.

The late Dr. Glenn Kahle, a lead engineer for Deere at the time, was put in charge of the program, and in an interview with me in September 2014, he recalled developing a combine that not only offered rotary separation, but also could be built with articulation and the ability to tow grain carts.

“We had four-wheel drive and hydrostatic [going to] all wheels. It was a hell of a machine.” Kahle said. Deere ultimately determined the investment to create the new machine was too expensive.

“The financial guys at Deere looked at their balance sheet and . . . elected not to go ahead with it,” Kahle said. “Which was one of the smaller reasons I actually left and went to IH.”

Driving home with a head full of stories and inspired by my recollections and experiences, the cold struck me as crisp and invigorating, a life-affirming reminder that you have to weather a few storms to figure out the puzzles worth solving.

Sketched by Mel Van Buskirk, this machine was designed to use rotary separation to shell corn in the field. The resulting experimental machines were built inside a secret garage on the grounds of the combine plant in East Moline, Illinois. The machines were tested from 1960 to 1962 and performed well in the field. Photo courtesy of Case IH

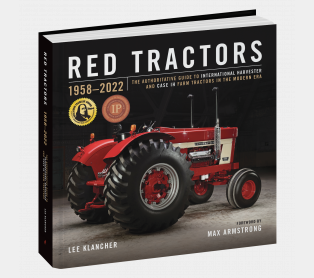

If you would like to read more stories like this one, check out the Related Books linked below.